String crossing and shifting are two fundamental techniques that present stumbling points on their own. Put them together and they can become an unfortunate blemish in an otherwise good performance. Without the necessary co-ordination between the left and right sides which are performing different physical tasks and a thorough understanding of the positions visited, this particular technique will lack good tone and accuracy of rhythm and intonation. Amazingly, it is all too often skimmed over by teachers who assume that if their students are reasonably capable of each individual technique they will easily be able to combine them. Just because I can easily pat my head and rub my belly doesn’t necessarily mean I can perform both actions simultaneously!

The first step towards mastering any technique is to understand why it exists and what it will enable you to do. The simultaneous string-cross and shift presents itself in two particular situations. The first of these and typically the first time we encounter the technique in our study of the cello is when we play in more remote keys which eliminate the use of some or all of the open strings. The second is when we need to avoid open strings in order to play sustained passages with consistent tone and vibrato or to avoid awkward string crossing in faster passages. One of the great advantages of being able to manage this technique well is the significant increase in potential fingering patterns that become available, which means that we have a much better and more varied sound palette at our disposal.

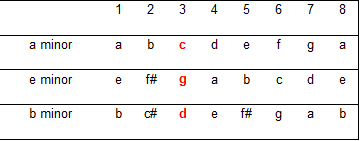

Most of us first encounter the need to shift and cross in scales: most notably, E Major. However students who play with orchestras frequently come across techniques they have not yet covered in their lessons and this is often one of them. To me it has always made sense to introduce the technique earlier on – while the neck positions are being studied – using home key scales such as F and D majors (two octaves) thus giving the student and early introduction to alternate fingering patterns and making remote keys far less daunting to play and sight-read. All it takes to comfortably manage a piece, study or exercise in a key with four or more sharps or flats is a sensible fingering pattern and the instinct to determine where extended positions are required – a simple matter of knowing where you are in the given scale.

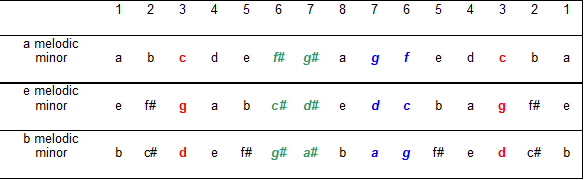

I believe the reason it is easier to learn scales such as D or F majors with fingering patterns that avoid open strings is simply that they are already familiar territory. Furthermore, there are open string targets available to test intonation along the way. Any student who has been introduced to the first four positions on the cello should be comfortable with major keys containing up to three sharps and two flats, and minor keys with two flats and one sharp. They will also have covered extended positions; and string-crossing* is one of the first techniques we are introduced to on the cello. By combining these techniques we can introduce the valuable technique of simultaneous shifting and string crossing to avoid open strings.

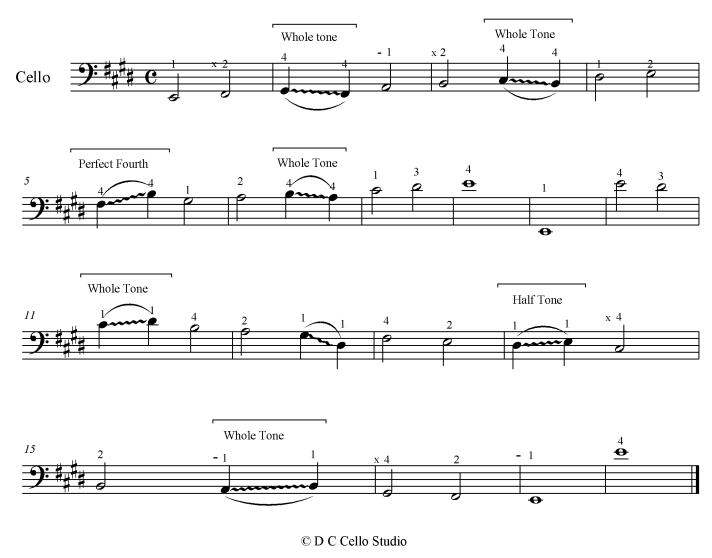

Below are two versions of the scale of F major (two octaves); the first with conventional fingering and the second with a fingering pattern that avoids open strings and happens to be identical to the conventional fingering of E major (two octaves), thus making F major an ideal means of preparing for E major.

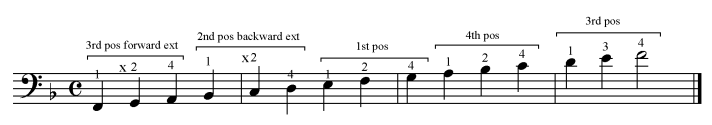

In the second fingering pattern, each string cross coincides with a position change. Most students find this confusing at first because with the exception of the shift from first to fourth position on the D string, backward shifts lead to a higher pitch in the ascending scale and visa-versa in the descending scale. So to grow accustomed to this counter-intuitive event, the following exercise can be practised until the left hand knows precisely how to move from one group of notes to the next.

Once you’ve mastered this exercise, you should be able to play the new F major fingering pattern fluently with no obvious gaps at the string crosses. Don’t rush: if you can’t play it slowly, there’s no reason why you’d be able to play it three or four times faster! Learning new shifts and fingering patterns, along with hearing the pitch you’re aiming for before playing it takes time and careful, well-planned practice.

The next step is to apply the F major exercise to the scale of E major as follows.

*The fact that it remains one of the most important and subtly difficult techniques to master is another article entirely!

© D C Cello Studio