For those of us with classical music training the concept of improvising often inspires feelings ranging from uneasiness to abject terror. We spend so much of our time bound to complex scores laden with incredibly specific instructions that the concept of making it up on the spot is foreign and frightening. Depending on what you do as a musician, you may never be confronted with a situation that requires you to improvise and therefore never feel the need to explore this avenue of music. If this is the case, you may be missing out on an enriching and satisfying experience.

I took it upon myself to develop my improvisation skills over a decade ago whilst at Music College. I was approached by an experimental poetry performance group from the local drama school (every bit as pretentious as it sounds) who were looking for a musician to provide incidental music for their tortured performances. I was intrigued by the idea and suggested playing excerpts from the Bach Solo Suites, which met with rolled eyes and long-suffering sighs – clearly everyone they’d already asked to do this had made the same or similar suggestions. What they wanted was someone who could provide a musical interpretation of their words and actions in real time – no rehearsals, no preparation and no sheet music. Just turn up and play. Up until this point, my musical experience had been nothing but intense preparation – whether it was for exams, competitions, recitals or orchestra rehearsals, the idea of “winging it” was out of the question. I agreed to turn up for their next performance, partly out of curiosity and partly because my bank balance was always in dire need of resuscitation. A day before the performance date I began to panic about what I had agreed to do. With the exception of playing a few pop tunes by ear on the piano in my school days and exploring a few chord progressions in the privacy of my practise room, I had never done anything like this before – especially not on the cello. I seriously considered cancelling on the grounds of a phantom flu bug or similar. I hadn’t told anyone about this particular gig because although I had no solid grounds to base this on, I assumed it would meet with disapproval from my fellow students and tutors. After much internal agonising, my curiosity and poverty came out on top and I decided to give it a go. After all, if it didn’t work out I simply wouldn’t do it again.

Of course, I couldn’t resist attempting a bit of preparation. I sat down with my cello, thinking I could perhaps come up with a few melodic ideas to store up my sleeve, but everything I tried sounded suspiciously like a medley of the repertoire I was studying at the time. The harder I tried to sound original, the less original I sounded. For fear of allowing my nerves to get the better of me again, I gave up the prep work for a bad job and hoped it would be all right on the night. It was better than all right. The actual performance (or what I can remember of it) was unbelievably over the top with painted faces, nudity, screaming and gratuitous profanity. I’m certain that had I recorded my playing I would cringe listening back to it. But I discovered my ability to let go of my classical paranoia, ignore the little voice that bawled at me when notes weren’t pitch or rhythm perfect and express my inner musicality on my instrument of choice. I continued to work with the tortured poets for the rest of my college days and thus began my fascination with an age-old musical discipline.

So if improvisation is about letting go of the rigidity imposed on us by classical music is it right to call it a discipline? Perhaps not if we’re talking about my first dabbling where I had no other musical lines to mesh with harmonically and simply tried my best to reflect what was going on around me. Compare this to the dazzling performances of well-trained jazz musicians however and you might as well compare a child taking its first steps with an Olympic athlete. After 12 years of developing my improvisation skills and putting them to the test in a variety of different musical settings, I’m no jazz improviser because jazz is not a genre I have had any exposure to other than listening to it. But I have learned to improvise confidently over traditional western diatonic and modal harmony, making my skill applicable to a wide range of styles and genres and ultimately making me a better rounded musician on numerous levels. Developing this ability has been a long road of trial and error and depended on two key ingredients: listening and following my instincts. Many believe that the ability to improvise cannot be taught and is based purely on musical instinct and aural ability. Whilst I can’t disagree that high aural aptitude makes improvising easier, I also know from my experience as a teacher that anyone capable of basic pitch recognition can develop that skill to recognise intervals, chords and modulations – the very same skills required to improvise. Most classical musicians get a good dose of theoretical and aural training to complement the study of their instrument, and all of these skills can be put to work to practise and improve our ability to improvise freely.

So where to begin? As previously mentioned my education in this discipline has been pretty haphazard and is by no means an ideal template to follow. After my early attempts at improvising on my own, I began to wonder how I would fare playing with other musicians. An opportunity arose to do a few jam sessions with a local blues band and I eagerly (if nervously) took it. I had a whale of a time, quickly learning the blues format and adjusting my style of playing to blend with the sounds of the lead guitar and the vocalist. It was probably fortunate that for the first few sessions there was no microphone available for me, and my cello was drowned out by the amplified guitars, bass and drums. This gave me the freedom to hit bum notes, misjudge chord progressions and generally make mistakes without upsetting the well-rehearsed harmony of the band. By the time a microphone was placed in front of my instrument I had become more familiar and thus comfortable with the style of the music and format of the songs and even felt confident enough to play a few solos when the opportunity arose. Having been given a confidence boost by doing the poetry performances, this was a brilliant start to my education and I would recommend it to anyone keen to try improvising on their instrument. Of course I realise there are a few flaws in this recommendation: not everybody lives in an area where such jam sessions might take place, not everybody likes the idea of playing along to a loud blues band and many, no matter how keen to try, do not feel confident enough to attempt improvising with other musicians when they’ve never tried it before. So here are my suggestions for getting started.

Many of us improvise without even realising it. Take the cacophony of an orchestra at the start of a rehearsal before tuning up. If you were to go around and listen to each individual player you would hear their own tailor-made warm-up routine which normally consists of a combination of scales, chromatic runs and arpeggios seamlessly running into each other. Sort of like a “best of” scales and arpeggios number, not methodically going through one scale after another in a cycle of 5ths but skipping from one to another. Everyone is doing their own thing, no-one is listening or appraising, and so if you were to record some of the individual warm-up routines, you’d probably hear some interesting and refreshing musical ideas that would surprise the players themselves. Anyone who has played in an orchestra will probably have done this to some extent. Next time you sit down to practise, give this a try. Instead of using a methodical list of scales or technical exercises to warm up, try creating your own routine with a mixture of scales, arpeggios, diminished 7ths, etc in different keys and tempi. The trick is to not think too hard about what you’re doing – pick a comfortable key and range to begin in and see where it takes you. Don’t be put off by notes that sound “wrong” or out of place and don’t be surprised if what you’re playing ends up sounding a lot less like scales and a lot more like a melody line. Don’t be despondent if the melody line resembles whatever repertoire you’re might be working on. Improvisation is also about being able to mimic a style, and you’re most likely to be able to mimic the style of the music you listen to the most.

This brings me to one of my earlier mentioned key ingredients: listening. Pick a style you think you’d most enjoy improvising to and listen to it intently and frequently. Start your own jam sessions – hum along to the music and see if you can develop an alternate melody line or harmonise with it. If you can vocalise your musical ideas, you should be able to play them on your instrument. If singing is really not your thing, go straight to your instrument and try playing along. Don’t be tempted to cheat by looking for sheet music even as a basic reference. It is up to you to use your listening skills to determine what key it’s in and what chord progressions it follows. Because this exercise is all about listening and not looking (at a score), try closing your eyes while playing along. Shutting out the world and its many distractions can’t hinder and may help to enhance how you listen and what complementary sounds you hear in your head. If you’re undecided on what genre to play along with, try blues. Even if it’s not a style you’ve ever paid much attention to, it’s an excellent place to start as it follows an easily recognisable format and chord progression. Try learning a few blues scales to complement your jam sessions and build up your musical ideas.

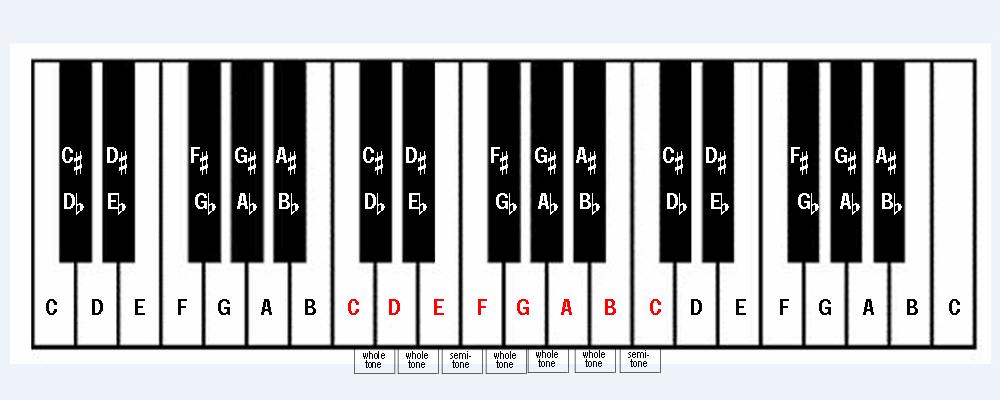

For developing your improvisation skills over conventional Western harmony, harmonised scales are an excellent place to start. Follow this link to download play-along scale recordings and chord sheets. You’ll find three separate exercises covering scales in major, harmonic minor and melodic minor keys respectively. Each exercise consists of 1 octave scales working chromatically through all 12 keys and a corresponding chord sheet. It is useful to print out and follow the chord sheet when doing these exercises, as it will help to develop your chord recognition. Instead of providing the actual chords for each scale in every key, there is one series of chord symbols which apply to every scale and key in the exercise. You can begin improvising a melody over the chords straight away if you’re feeling bold, or (and I recommend this) you can start slowly and just play the scales at first, making sure that you read and take in each chord as you play each note. The scales are deliberately slow to give you time to listen to and take in each chord and later on to put in interesting passing notes and/ or chord extensions to make your improvisation sound more interesting. This is where instinct comes in. Whilst it is very useful and often necessary to understand and recognise the chord progressions you’re working with, it is equally important to be able to stop thinking about the theory and trust your musical gut. After all, you’ve been listening to and playing music for years. We all store up the parts we like the most or find the most distinctive from music we come into contact with and improvisation is a wonderful way of expressing those preferences. This, like interpretation of great classical works, is personal and once you have guidelines to get your creative juices flowing, cannot be taught.

Once you’ve spent sufficient time working on the scales and growing your confidence in your ability to create on the fly, it is probably time for you to seek out other musicians to work with. Again, the type of musicians you look for will be entirely up to your taste and aspirations. You may just be trying out improvisation to see whether you can do it or not, to broaden your musical horizons. If this is the case, you may feel that there is no real need to go outside the privacy of your bedroom, but I’m willing to bet you’ll find it more satisfying jamming with others, exploring each other’s musical styles, comparing notes and encouraging each other. If your aim is to take your improvisation to the stage you absolutely have to find others to develop your skill with first. It’s all very well being able to play pleasing melodies over a predictable chord progression, but the next step is to put yourself into a much less comfortable setting and learn to listen to and predict what others in your group will do. This may sound daunting, but in all likelihood you’ll start by agreeing on a basic chord progression to get warmed up and your jam session will evolve organically from there. You’ll probably be surprised at how far the music eventually wanders from your originally agreed structure and how once you’ve become more used to each other’s musical styles and ideas; you literally seem to be able to read each other’s minds.

Most who try this wonderfully liberating practice will derive something useful from it even if only to break away from the inherent fetters of classical music. As a cellist, learning to improvise has improved every aspect of my playing and musicality. The more I have explored and practised it, the more I believe that it should be incorporated into classical music training.

© D C Cello Studio