We all have different levels of motivation, and these can vary a great deal according to circumstances such as the time of day, emotional well-being, physical well-being and workload. If you’re the type of person who has the right combination of organisation and drive to keep your practice routine regular and effective, you probably don’t need to read this. If you’re anything like me you’ll have times when your practice routine is smooth and enriching, and times when opening your cello case seems like a challenge on a par with climbing a mountain. I believe everyone has the odd day like this, and it is important to allow ourselves a bit of time off when we simply don’t have the stamina and concentration necessary to practise well instead of dragging ourselves through a frustrating and unprofitable practice session or feeling guilty about missing a session.

When we encounter days, weeks or even months of sporadic practising and low motivation it is important to make every effort to understand why, and to find ways to reignite the spark. Throughout my career I have encountered bad patches where I feel as if I’ve run out of steam. I’ve seen it happen to many of my students at some point too – sadly some of them were unable to get back into a progressive routine and decided to call it quits. I’ve also had my fair share who were on the brink of giving up and after regaining their inspiration, were back on track and better able to cope with future dips in their motivation.

Since there are many potential reasons for loosing motivation to practise, and it’s often difficult to determine the cause straight away, you might find these questions helpful:

1. What am I working towards?

This always tends to vary quite a lot for young progressing cellists: there are orchestra auditions, seating auditions, recitals, competitions and exams to name but a few of the challenges that feature in a young musician’s busy schedule. If one of these is looming ahead and you’re feeling reticent about practising even though you know you still have work to do perfecting those tricky sections, perhaps your fear of the event is getting in the way of your progress. It helps to remind yourself that no matter how scary and life-changing that audition, recital or exam might seem, it’s only one of many milestones along the way. Try to think beyond the event itself: what piece do you hope to be learning in six months’ time? Or remind yourself of previous performances that have gone well for you: think about how you felt and what your routine was like in the weeks before the performance.

Perhaps your problem is the opposite of this. You may feel that all you’re practising for is your lessons, and that your teacher has not given you any milestones to work towards. This can be a major cause of losing motivation and even interest in playing your instrument. Speak to your teacher about it! Perhaps when you started out you specified that you were not interested in playing exams and just wanted to learn for fun. It is fine to change your mind about this, but your teacher is not a mind-reader and will not put you forward for potentially stressful playing opportunities or challenges if he/ she thinks that you don’t want to.

2. What have I been struggling with in my recent practice sessions?

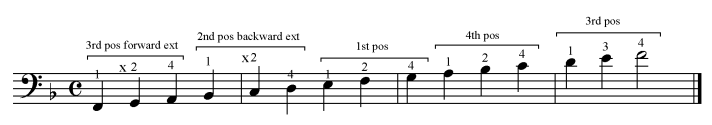

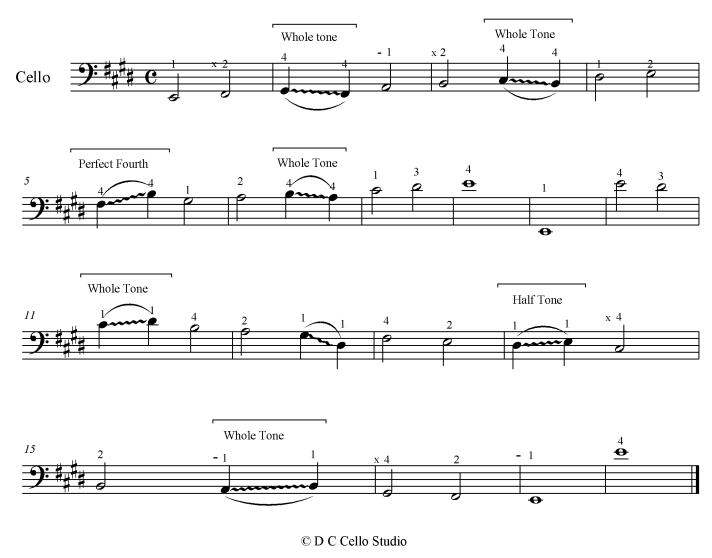

I have often found that when something just isn’t improving from one session to the next I start to feel despondent about my playing in general and I have seen this in other cellists too. Of course some things take longer to get to grips with than others, and those of us with a less patient temperament may simply be expecting too much too soon. But when a technical issue constantly puts a blemish on the repertoire you’re working on, it can be incredibly frustrating and demotivating. If you’re taking lessons you will no doubt have discussed it with your teacher, who will hopefully be exploring new ways for you to approach and understand the problem. Remember that you should also take some responsibility for your learning process. Your teacher sees you once a week or less and cannot be there to guide you every time you sit down to play or practise. You need to be your own teacher outside of your lessons, and when you hit a brick wall you should do what any good teacher would do: read as much as you can on the subject and ask other cellists for advice. Look for footage of great cellists containing the technique you’re struggling with and watch it over and over again. If possible, watch it in slow motion, or pause it at crucial points to observe the player’s posture and balance. Bring your observations to your lesson and discuss them with your teacher so that between you, you can come up with a new ways to learn and master a challenging technique. This problem-solving approach can be a wonderful means of reigniting that magical spark as it always leads to discoveries – not only about your playing and practising habits, but also about yourself.

3. Am I struggling to motivate myself elsewhere?

We all face those periods of low ebb where we feel exhausted all the time, struggle to concentrate for longer than five minutes at a time and generally need a holiday. If getting away for a few relaxing days isn’t an option, try “micro-holidays”: go for walks, take time out to watch your favourite film and try getting earlier nights. You’ll know best what helps you to relax and when you need to rethink your daily routine.

4. Is my instrument holding me back?

Is your instrument in need of a fresh set-up or even an upgrade? It is often said that only a poor workman blames his tools and sometimes that is very true where musicians are concerned. I once worked with a conductor who fined any member of the orchestra (in his preferred currency of a pint) who dared blame a mistake on their instrument. But if you’re playing on a cello with a poor set-up, a warped or balding bow, or an inferior instrument that simply doesn’t stand up to the technical demands of your repertoire it is more than fair to blame your tools. As an example: a cello with excessively high string to fingerboard action is the worst enemy to left hand technique, especially for smaller hands. If you’re fighting with your cello every time you try to play it, it’s highly unlikely that you’ll be looking forward to your next practice session.

There are many other factors that can and do influence how we feel about practising. Some of these are covered in my earlier posts on this subject: Effective Practising – Warming up, Making the Most of Your Time, and Tips for Cooling Down. This and the previous posts by no means cover the entire topic. I recommend The Advancing Cellist’s Handbook by Benjamin Whitcomb as a comprehensive guide to practising for intermediate cellists.

Did you find this post useful? Please consider making a donation.

© D C Cello Studio 2011