Practice makes perfect? Well, that really depends on the quality of the practice sessions. We all know that without practice there is no progress – playing a musical instrument is a never-ending learning curve. But we also know how hugely frustrating it is when we’re putting in hours of hard work and feeling a distinct lack of progress, or perhaps even a sense of one step forward three steps back. If this is the case, the first thing you need to examine very closely is how you practise. It’s a sad fact that many teachers offer outstanding advice and wisdom in lessons but forget to teach their students how to practise. For some students there is little need to focus on the art of practising, but for most of us it is not a natural skill. And the more time we spend doing something incorrectly, the harder it becomes to undo the damage.

So what makes a good practice session? Quite simply, it is time spent reinforcing and ideally improving on a technique, a section of a study or even half a bar of a piece. How is this achieved? That really depends on you as an individual and how you learn best. But fortunately there a few constant rules that apply to everyone regardless of skill level or personality type.

Warming Up

You wouldn’t start any kind of physical exercise or sports session without warming up, so why should your cello practice session be any different? Just because you’re spending the session sitting down doesn’t mean you wont be engaging in intense physical activity. Those new to cello playing may not be doing anything acrobatic on the instrument just yet, but they will be using muscle groups in ways that they are not accustomed to. More advanced players find themselves performing complex physical tasks which depend on the muscles being warm. You’re just as likely to injure yourself by launching into complicated, blindingly fast scale and arpeggio exercises as you engaging in any intense physical activity such as running or dancing without warming your muscles up first.

Warming up can be done just as effectively away from your instrument as it can doing dedicated warm-up exercises on the cello. During the cold winter months warming your hands before getting down to any serious playing is essential and can be achieved by doing gentle finger exercises in a basin of warm water or whilst wearing thermal gloves. The following exercises are great for getting the blood flowing to the fingertips:

- Alternate between making a fist (not too tight) and stretching the fingers out

- Flicking each finger against the thumb

- Gently squeezing juggling balls or anything of similar size and malleability

- Hold a squash ball in the palm of your hand and gently push each finger against the ball

Balancing and breathing exercises are an excellent way to get your body in the ideal state for playing. As cellists we easily forget the importance of regular deep breathing when we play and all too often unwittingly hold our breath when we’re wrestling with difficult passages or new techniques. Soon the shoulders become tight and hunched, and nothing good can come of that. Breathing exercises for singers are perfect and easily found all over the Net. Combining slow controlled breathing with simple balancing exercises is a great way to focus on posture and finding our centre of gravity, without which all playing is severely limited. When I say simple, I mean simple. Don’t feel that you need to consult advanced pilates, yoga or martial art manuals. Standing on one leg for a few seconds, then switching legs and repeating the exercise attempting to increase the time spent balancing on each leg. Having a mirror in front of you will help you to ensure that you are standing tall, keeping your shoulders relaxed and square, and your head on top of your spine (as opposed to inclined or slightly in front of your spine). You can also step things up a little by gently swinging your arms to and fro, ensuring that they move freely with no restriction in any of the joints.

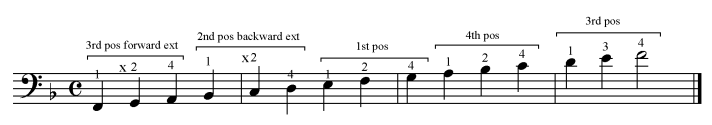

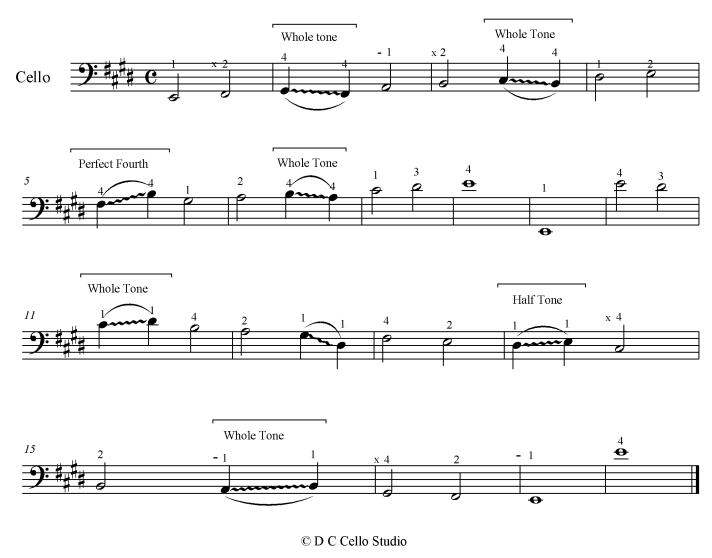

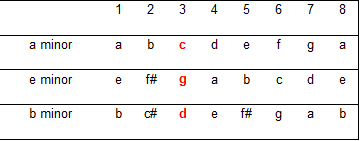

Warms-ups on the cello should engage both left and right hand, but not necessarily at the same time. It is perfectly acceptable to begin with bow warm-ups on open strings, or bow exercises without the cello itself (a fine example of this is on the very first page of Christopher Bunting’s Portfolio of Cello Exercises Book 1). Using a metronome to time bow strokes and maintain discipline is something I can’t recommend enough. Not only is it an important means of keeping your exercises precise, it also helps to develop a keen sense of timing and speed in your bow technique, which will make all the difference in your search for a beautiful and artistic sound. Again, I refer you to the first page of Bunting’s Portfolio Book 1: the bowing regime. I’ve had a job and a half convincing my students to make this dry, seemingly dull approach to bowing part of their daily warm-ups. But those who have succumbed to my endless nagging have come back beaming, especially once they have been doing it for weeks or more and begun to feel and hear the difference it makes to their playing. It makes sense to find warm-up exercises that serve more purpose than simply waking up the muscles and getting the blood flowing to the extremities. I guarantee that the bowing regime does just that, and I strongly recommend reading Bunting’s Essay on the Craft of ‘Cello-Playing for a detailed description on approaching the exercises. Of course the left hand needs warming up just as much as the bow arm does, and should also be given a gentle wake up rather than overly demanding exercises. I find the trilling exercises (number 1) in Feuillard’s Daily Exercises for Cello to do the job very nicely. For the purpose of warming up I ignore the fast variations and stick to the quaver exercises, which I do on all strings and in all of the neck positions. Again, the metronome is crucial as a means of keeping the finger work steady and balanced, preventing any urge to speed up. I find it equally beneficial replacing trills with slow timed vibrato on each finger, each string, and in each position – either working through the neck positions or through the mid-positions (5th to 7th).

Not only should your warm-up session perform the obvious task of warming the muscles and getting you physically prepared for a good practice session, it should relax you physically and mentally, helping you to focus your mind on what you wish to accomplish in the following 40 – 60 minutes. The amount of time you spend warming up depends on how long you plan to practise for, and how demanding your practice material is. I recommend a minimum of ten minutes for your first hour long session of the day; and at least five minutes for each subsequent session.

© D C Cello Studio