Firstly, let’s define three important terms which are easy to get confused and therefore important to be distinguished from each other before exploring how they are related.

1) Key: a family of notes which belong together and have a distinctive sound or “colour”. A key can be major or minor and is represented by a key signature (see definition 2). Every key has 7 individual notes which are represented in the scale (see definition 3) of the key.

2) Key signature: a representation of the accidentals found in a key. These are shown at the start of each stave just after the clef and just before the time signature* and greatly reduce the number of accidentals that have to be shown in the main body of the score**. The order of accidentals in a key signature does not always follow the order in which they appear in the scale. Instead, they follow the order in which they appear from one scale to the next.

3) Scale: a representation of the notes belonging to a key in ascending and descending order starting and ending on the root note of the key. There are 3 main types of scales: major (which represent major keys), harmonic minor and melodic minor (which represent minor keys). Each type follows a specific order of intervals***

* Times signatures, unlike clefs and key signatures, are only shown at the start of the first stave and do not appear again unless there is a change of time signature in the music

** Score: a written or notated representation of music

*** Interval: the pitch distance between 2 consecutive notes (e.g. C – D = a whole tone or major second; C – D-flat = a half tone or minor second)

Understanding major and minor keys and their relationships

The reason there are related major and minor keys is because they share the same key signature. Major keys are easier to understand because they do not deviate from their key signature, and have only 1 scale to represent them. Major scales are based on the following sequence of intervals:

Whole tone; whole tone; half tone; whole tone; whole tone; whole tone; half tone.

So let’s see how that relates to the actual notes of C major:

C – D: whole tone

D – E: whole tone

E – F: half tone

F – G: whole tone

G – A: whole tone

A – B: whole tone

B – C: half tone

Now let’s look at F major:

F – G: whole tone

G – A: whole tone

A – B-flat: half tone

B-flat – C: whole tone

C – D: whole tone

D – E: whole tone

E – F: half tone

So no matter what the key, major scales follow an identical sequence of intervals. This is why they all have different key signatures. In order to follow the same sequence, they have to follow a unique pattern of notes.

Minor keys are more complex than major scales. Every minor key has 2 different types of minor scale as previously mentioned: a harmonic minor scale and a melodic minor scale. Each type of scale deviates from the key signature in a slightly different way.

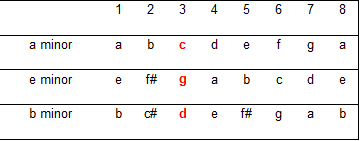

But let’s forget that confusing fact for a moment and look at how major scales and minor scales relate to each other. Every key signature relates to both a major key and a minor key. The table below shows 3 ascending major scales. The numbers above the scales relate to the steps of the scales. The red note in bold print in each scale is the root note of the relative minor.

You’ll notice that it is always the 6th step of the major scale that is the root note of the relative minor key. This is the easiest way to find out which minor key shares the key signature of a major key.

In contemporary rock and pop music, we often come across “natural minor” scales (also known as the aeolian mode). These are minor scales that do not deviate from the key signature and take on the following sequence of intervals:

Whole tone; half tone; whole tone; whole tone; half tone; whole tone; whole tone.

This is a (natural) minor, which is related to C major (as you can see in the table above)

A – B: whole tone

B – C: half tone

C – D: whole tone

D – E: whole tone

E – F: half tone

F – G: whole tone

G – A: whole tone

The next table shows the three natural minor scales related to the major scales above. This time, you’ll notice that the bold print red note, which is the root note of the relative major key, has changed to the third step.

In classical music, minor scales are altered in 2 different ways. This gives minor keys a more distinct and defined sound, and distinguishes them from major keys. The first alteration is the harmonic minor scale, in which the 7th step is always raised up by a half tone as shown in a harmonic minor below:

A – B: whole tone

B – C: half tone

C – D: whole tone

D – E: whole tone

E – F: half tone

F – G#: augmented second

G# – A: half tone

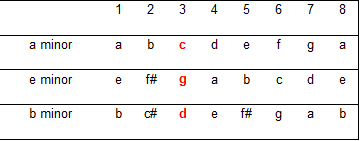

The augmented second is the largest interval you’ll find in any classical scale, and is only found in the harmonic minor. Play and listen to the scale several times to hear its distinct sound. The table below shows 3 examples of harmonic minor scales. The altered 7th steps are in bold italic.

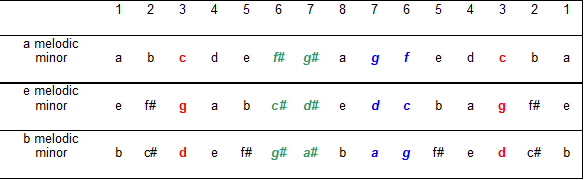

Now for the melodic minor scale, which I like to call the chameleon scale because it changes its colours on the way down. Melodic minor scales raise the 6th and 7th steps by a half tone in the ascending half and lower them back down by a half step in the descending half. This means that the scale has a different sequence of intervals in its ascending and descending halves as shown in a melodic minor:

Ascending

A – B: whole tone

B – C: half tone

C – D: whole tone

D – E: whole tone

E – F#: whole tone

F# – G#: whole tone

G# – A: half tone

Descending

A – G: whole tone

G – F: whole tone

F – E: half tone

E – D: whole tone

D – C: whole tone

C – B: half tone

B – A: whole tone

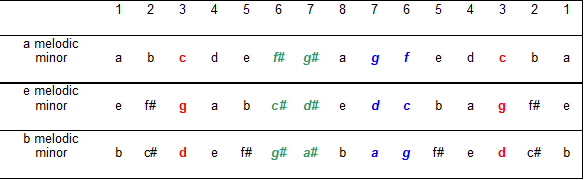

Note also that the descending melodic minor scale is a natural minor which follows the key signature. Play and listen to the scale, and be sure to hear the difference between the melodic minor and the harmonic minor. The table below shows 3 examples of melodic minor scales. The relative majors are once again marked in bold red; the altered notes in the ascending scale are shown in bold italic green, and the lowered notes in the descending scale are shown in bold italic blue:

The altered notes in harmonic and melodic minor scales are always shown as accidentals within the score, and not in the key signature.

So how do we know whether a piece of music is in a minor key or a major key? First look at the key signature and make sure that you know which major and minor key it belongs to. Then look at about the first 8 bars of the music. If you see any accidentals within the score (not, the key signature – you’ve already looked at that) check what they are. If they happen to be the 6th and/ or 7th step of the minor key, then you can be certain that the music is in a minor key and not a major key. If you see no accidentals within the score, or accidentals that are not the 6th or 7th steps of the minor key, you can be certain of it being a major key.

© D C Cello Studio

© D C Cello Studio