“Intonation is a question of conscience.” – Pablo Casals

So true on so many levels! A burning issue for all us bowed string players and the bane of many of our lives, intonation tends to remain a work in progress for many years. When examined up close this topic becomes less of a discussion and more of a doctoral thesis. And like so many aspects of cello technique, you’ll encounter significant differences of opinion amongst players and teachers on how to tackle intonation problems.

I suppose this comes as no surprise – when I try to analyse precisely how I play in tune (I should point out that even after twenty-four years of playing this doesn’t always happen), I’m frankly stumped. There are obvious elements essential to good intonation such as accurate finger placement, an excellent grasp of the geography of your cello and well developed relative pitch (assuming you don’t have the rare gift of perfect pitch). But there is definitely more to it than that. Casals called it a question of conscience. Bunting suggests (quite refreshingly) that perfectionist attitudes to intonation annihilate freedom of movement in the fingers essential to so much more than just intonation. Both philosophies point to something other than a technical or mechanical process. There is a strong psychological aspect which I believe is all too often forgotten or discarded.

We all have specific feelings about intonation. For many of us those feelings may include fear, frustration and often denial – leading to a high tolerance for inaccurate tuning. Perhaps the ideal relationship with intonation is to view it as part of the artistic palette. Emphasising certain intervals (such as marginally sharper major thirds and sevenths in major keys, or flatter thirds in minor keys) can colour and define keys quite beautifully. To reach this ideal I believe one has to allow for a margin of error, which gradually diminishes as the physical memory becomes more accurate and the ear more exacting. This allowance should not be confused with the previously mentioned tolerance for poor intonation, which I have seen developed to an alarming degree in some cellists despite most of them having a “good ear”. For a long time I was one of those intonation “deniers”, often thinking my performances had gone rather well only to listen back to those which had been recorded and cringe in horror at the glaring intonation errors.

Based on my own playing experience and that of my students, I believe there are three main negative emotions associated with poor intonation: fear, uncertainty and low self confidence. The first two are relatively easy to combat (although they take time to get rid of); the latter is trickier and varies a great deal from one individual to the next.

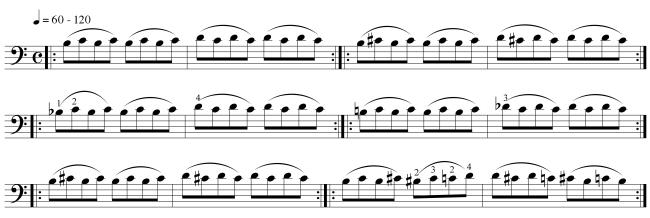

So, fear and uncertainty first! High register playing and large interval jumps are prime candidates for inspiring apprehension, which lead to physical tension, and we all know what impact that has on intonation. Take your pick of the major cello concertos for passages in the instrument’s upper range. How often do we hear (or give) performances of these works that are let down by those upper register passages when the sound is thin and some or all of the notes are off-pitch? Even after hours of repeating those passages ad nauseam in the practice room, they often let us down in performance. All too often the practice we do to eliminate the fear factor only perpetuates it. The root of the problem is not in the passage, but in the irrational fear of that portion of the fingerboard. So it stands to reason that getting familiar with that highest octave-and-a-half through slow, relaxed work on scales, arpeggios and studies is a much better use of our practice time than repeatedly trying to play a phrase or passage in an area of our instrument that frightens us because we don’t know it well enough. No matter how hard we try to make it sound beautiful, our attempts are undermined by inaccurate finger placement and incorrect bow placement. With enough repetition of the same high register passage, we might eventually become more familiar with that area of the cello. Equally we are in danger of constantly reinforcing incorrect finger placement and excess tension because our focus is more on trying to play the passage the way we think it should sound and not nearly enough on the mechanics behind the music.

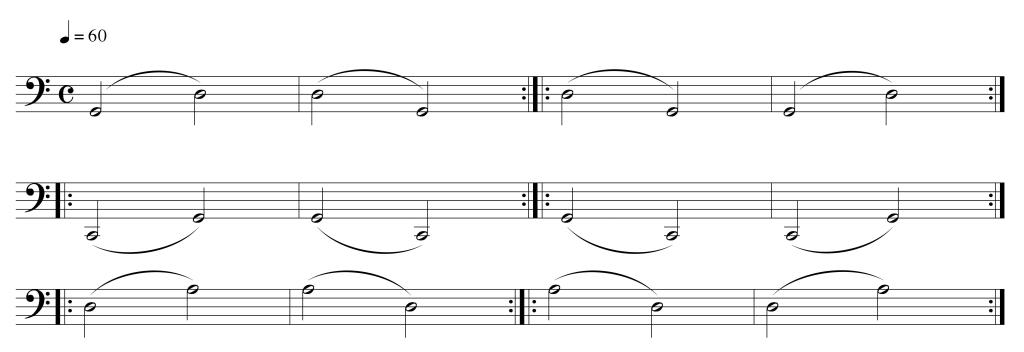

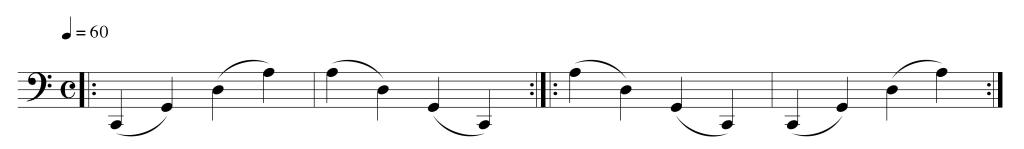

There is certainly no shortage of technical material for the cello that covers the entire range of the instrument or concentrates on perfecting the upper register – Feuillard’s Daily Exercises for Cello, Yampolsky’s Violoncello Technique and the Galamian Scale System for Cello to name a few. Until we can comfortably play such technical material covering every inch of the fingerboard, it is unreasonable to expect ourselves to be able to play repertoire with these technical demands. However you choose to approach familiarising yourself with the full range of your cello, familiarise yourself you must and you really are better off using a method designed specifically for this purpose. When Elgar was composing his sublimely beautiful cello concerto I seriously doubt he ever stopped and thought: “Ah, this will do wonders for the bow technique!” He composed the work with those whose technique was already fit for purpose in mind. But I’m digressing somewhat. The point I’m trying to make is that through consistent, concentrated practising of scales and arpeggios of every shape and size we give ourselves a much better chance of making that magical and essential connection between internal pitch and physical memory – the marriage between the sensitive fingertips and attentive ears.

Low self confidence, as I’ve already pointed out, is a more elusive problem which can have its roots in such a vast range of places that it is not really possible to tackle with a single suggestion. I do believe however, that investing enough of one’s time in the aforementioned study of the fingerboard will at least serve to relieve some of the symptoms of the problem. I also know from my own experience and from watching my students develop, that intonation is often bad because we expect it to be. That expectation is built up over years: the majority of us start out with poor intonation, not because we can’t hear it but because we don’t know where or how to place out fingers. For some cellists the development of a dependable left hand technique happens in a nice upward trend and their fear of intonation disappears as their command of the instrument improves. But for many more – perhaps most – it is more of a jagged affair with frustrating flat lines and almost as many downward as upward spikes. Surely this trains us to feel negative about aspects of our playing and gives us reason to believe that we are more likely to be wrong than right in the placement of a finger or a shift to a new position.

Again, I refer you back to the good old-fashioned daily dose of scales and arpeggios. Add a metronome to that, and remember: it is impossible to practise too slowly whereas practising too fast is not only possible, it’s disastrous.

Did you find this post useful? Please consider making a donation.

© D C Cello Studio 2011