Cello students who have studied the entire range of the cello will almost certainly have discovered a recurring pattern of similarity between certain positions one octave and string apart. Recognising this pattern can be very useful when it comes to getting secure in the higher positions, the fear of which often causes poor intonation and inferior tone production. The pairing I’ll be discussing in this and the following four posts is as follows:

1. First and fourth positions:

1.1 First position on the D string and fourth position on the A string

1.2 First position on the G string and fourth position on the D string

1.3 First position on the C string and fourth position on the G string

Also:

1.4 Half position on the D string and upper third/ lower fourth position on the A string

1.5 Half position on the G string and upper third/ lower fourth position on the D string

1.6 Half position on the G string and upper third/ lower fourth position on the D string

2. Second and fifth positions:

2.1 Second position on the D string and fifth position on the A string

2.2 Second position on the G string and fifth position on the D string

2.3 Second position on the C string and fifth position on the G string

3. Third and sixth positions:

3.1 Third position on the D string and sixth position on the A string

3.2 Third position on the G string and sixth position on the D string

3.3 Third position on the C string and sixth position on the G string

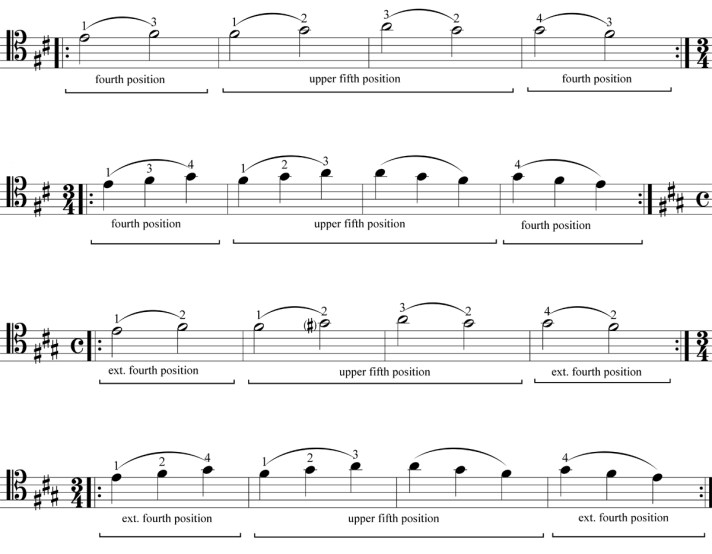

4. Fourth and seventh positions:

4.1 Fourth position on the D string and seventh position on the A string

4.2 Fourth position on the G string and seventh position on the D string

4.3 Fourth position on the C string and seventh position on the G string

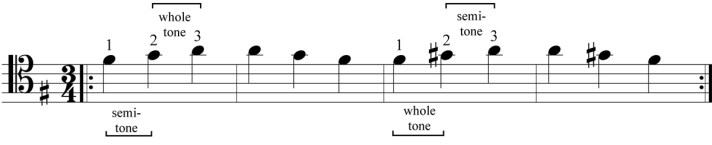

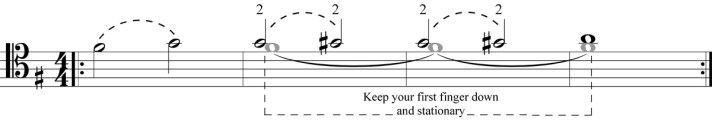

The first pairing (first and fourth positions) shares identical fingering patterns since both are neck positions. The same applies to lower second and lower fifth positions. From extended fifth position onwards, the three finger system comes into use, so the notes of the paired positions remain the same but the fingering does not. The changes are as follows:

In the higher positions, the second finger plays notes that would be covered by the second and third fingers in the lower positions.

In the higher positions, the third finger plays notes that would be covered by the fourth finger in the lower positions.

This discrepancy applies to closed and stretch (or extended) positions.

The following four posts will show these pairings through simple exercises and melody lines.